Emily Jones, co-author of Earlyarts Creative EYFS teaching packs, talks to Ruth Churchill Dower about how the natural environment stimulates our natural creativity and how we can nurture this in our every day practice with young children.

Ruth: Tell us about what’s involved in your outdoors work at the Tinderwood Trust

Emily: My work is all about enabling children’s learning to develop in the most diverse creative situations. We try to embrace the fact that we live in an amazing world, that children should be in it as much as possible so they can learn from it by trying everything they can possibly try and learning from their mistakes whilst they’re in this outside environment.

That includes working with families, encouraging parents and children to play and learn together. Learning that way enables them to co-operate and communicate about issues such as risk, and negotiating what’s comfortable for each party. Through this, they can then figure out that being a parent of a young child is actually a fantastic position to be in because they see that their children are amazing.

Another part of our work is working with children in schools, trying to get them out of classroom situations so that children can be seen to thrive in outdoor situations. We also work with professionals to enable them to think more clearly about the learning opportunities that being outside offers children, and the innate response that children have to the natural environment – how that can nurture their creativity, their playfulness and their investigative enquiry of the world, and how they can communicate in ways that you just don’t see working with kids inside.

It’s also about getting children to appreciate the natural world around them. They’re going to be guardians of our green spaces and if they have no experience of how amazing it is to be inside a bluebell wood, how would they ever know that it’s worth protecting? So, in a nutshell, that’s what we do.

Ruth: How do you put these principles into practice?

Emily: Well, for instance, today - a rainy, autumn day in the Calder Valley - we made boats out of bark, with clay that we dug out of the ground, with leaves that had fallen on the ground, and with every kind of conversation imaginable about where the bark or clay came from, what kind of leaf is this, why is it on the ground and not on the tree, etc. We then floated the boats in a pond – the children all know how to navigate the pond safely by lying on their bellies. We also made water runs out of cutters because we wanted the boats to shoot a bit faster, so the kids understood then about capacity, and the movement of water.

That was only what I had planned to do. However, one boy came up to me and what he actually wanted to do was count the raindrops on a wire fence. He spent a long time doing this, and when he touched each raindrop and it disappeared, the wonder on his face was beautiful. My plans were nothing compared to his, because his held much more value for him.

We also had a volunteer story teller with us today who followed what we were doing with the children. Because it was a rainy day, we made a huge den with loads of knot tying, talking, and drinking hot chocolate! Then she told us a story about hot chocolate. So, in those terms, it’s really hard to quantify the number of learning experiences the children were engaged in because they learn so fast, but we can safely say there were a lot!

Ruth: In one session, you’ve covered so many different areas of learning, physical development, motor development, creative, personal, social or emotional development – it’s all in there. I guess the language development comes from articulating the experiences they’re having during these sessions?

Emily: The language and social development is really paramount, especially for small children, as they’re trying to find out how the structure of the world works. So, being able to play in ways that enable them to do this is important. Today, one child talked about how they could make their boat sink, and wondered what would happen if they put a rock on it. They found a rock, sunk the boat and then said that ‘rocks must not help boats to float’. The language development is huge on top of their physical and cognitive activity.

The kids are also learning how to keep themselves safe so, for instance, we have a treehouse which hasn’t got any sides on it and it’s a wet day so the wood is slippery. We told them to be careful of this and they were careful – we didn’t need to stand next to them all the time because we gave them responsibility to look after themselves and their friends. It’s a skill that doesn’t fit into any curriculum tick box but one which is essential in so many areas of life.

Ruth: What do their parents think of this approach?

Emily: Well, as far as I know, the parents really value the chance to play with their kids and also to be with other parents because there seems to be a sense that when you’re out in the open, you can have a bigger conversation than you can when you’re stuck in a church hall with lots of plastic toys around.

So a really strong connection seems to be developing between some of the parents. It reminds me of when I was little and we lived with our Gran – she used to chat to the neighbour in different gardens while I was playing and that sense of community of different adults doing their thing while keeping a watchful eye out for the kids, that seems to be what emerges at the family sessions we run.

We were working with school yesterday, which is a different kettle of fish. We worked within their theme of Egyptian gods and goddesses of things that were important to the children whilst playing outside. So the environment that is set for the adults there is more challenging because it could be too pre-defined by the curriculum outcomes they are trying to achieve. However, we find that when you set the question that is most important to find out within that theme, then enable teachers to stand back and try and approach it using an early years ethos throughout key stage one or two, this approach creates a big difference in the way teachers work because they see the big impact it has on their children’s understanding, which happens through active ‘doing’ rather than passive ‘listening’.

Ruth: Do you find that settings and schools continue that work once you’ve stepped out of the picture?

Emily: Yes - one of the settings we worked with for over a year is carrying on the work themselves. I heard through the grapevine that they have now gone on to offer Forest School activities which they weren’t trained in before we worked with them. We’ve helped redevelop another school area as part of our consultation on Learning Spaces, and I know now they are using that area as a planned learning space every day now. So we know there are lots of successes - even when it doesn’t involve us, the ethos of working with natural environments is carried on, and that’s great.

Ruth: Have you seen any surprising things happening that children have created, or comments by children or parents during this work, anything that stands out?

Emily: I’m constantly surprised by children – if I wasn’t life would be very boring indeed! I’ve repeatedly seen teachers stop and gawp at children and say, ‘Look at that! They would never have done that before!’ It’s often in relation to how children are engaging with their peers, directing their own play, or being part of a friendship group that they haven’t engaged with before.

Also, parents’ smiles and relaxed faces say it all. Plus the way time whizzes past in our sessions – three hours seems a long time but really it’s gone in a flash – which is always a good sign!

Ruth: If you could choose the three most important experiences for children’s learning what would they be and why?

Emily: I would say firstly giving a young child a massive stick and allowing them to smash the ice off the top of a pond. That’s really important to be given the permission to do that because ice and coldness is something we rarely experiment with. In my experience, the way play has developed from those type of instances has been fantastic – even going as far as children sculpting ice castles!

Another experience that’s really important is being able to give children space and time, whether that’s up a tree or sat next to the campfire watching the smoke going up into the sky. Those moments are times when you can sit quietly and reflect and just be. And it’s hard to quantify the value of it, but it is valuable and yet the ability to do that is getting less and less for children.

Also the experience of learning how to light a fire without any matches is top because of the perseverance and effort that it takes, and the thought behind why you need to get the fire going (the intention), which are all really, really valuable. The look on the child’s face when they make a fire themselves – that feeling of success, confidence and achievement - is something every child should experience as frequently as possible.

Ruth: I was thinking today that if we, as adults, don’t experience those moments of utter discovery and the sheer joy in the adventure of discovery, then we can’t necessarily create the environment for children to have those discoveries themselves because we’re always afraid of what might happen instead of knowing how brilliant it is when it does happen. So how can we just get adults out of the office, boots on, and more involved in this sort of approach?

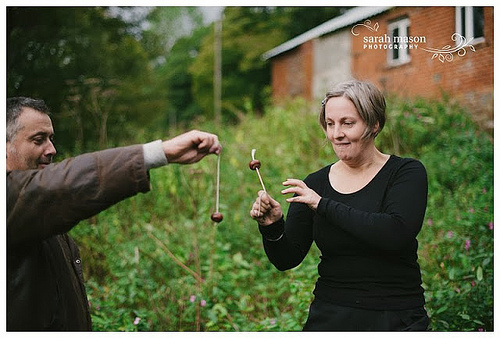

Emily: Yes, we do run training days for adults where we make fires, then make bread over those fires, spread on the jam that we make from the local fruit, play conkers, climb trees, get lost in the woods, damn streams, and so on. At the last professionals training day, out of 25 adults, 23 had never played conkers! So if adults are working with children, it’s crucial that they learn these playful experiences so they know what to expect with the children in their care, and how to raise their levels of expectation as to what’s possible for young children.

If they don’t understand how to feel the freedom and strength of their own playfulness, then how do we then enable them to translate this into creativity inside or outside of the classroom? We need to make sure that we try to raise the profile of playfulness and creativity in the training of early educators, in their continued development, and in the resources that are out there, such as in your own Creative EYFS teaching packs.

Ruth: Can I come and do it please?!How do people contact you to get into this approach?

Emily: There’s no particular process, most people find us through our website or our facebook page, which has got some amazing pictures of our children’s adventures. Then we have a conversation about what they need, and how we can approach this together. No two days are the same, they have to be designed to the meet specific needs of each setting or school, but this means the results are much more personal for everyone involved. We don’t teach the same way for all of our children. So why would we do that for the adults?

In terms of measuring our impact, we ask for feedback of how this approach has made a difference and why on each course or project. Plus we make sure we have constant communication with the teachers so that they can tell us what the kids have been taking about, so we can implement their ideas as part of the next session they spend with us. But I think it’s always hard to understand what makes the shift because who knows? We do what we do because we think it’s the right thing to do for children, and the kids tell us anyway what they enjoy most and what makes them happiest.

In fact, the best feedback is when you call the children into a circle to say it’s time to wrap up, and you’re met with so many groans because they don’t want to go! That’s our best evaluation of impact – when we get lots of ‘I can’t go yet, I’ve got this rope and it’s going to be my sky ladder…’ or ‘Can I come back because I haven’t finished my rain forest den yet’ – they’ve got a million and one things they’re still working on and are deeply engaged in. But that’s fine because we have enabled a supportive environment that they can come back to with their parents, or continue in other environments at school or home. It’s an environment full of risk, but it also reflects the real world that they’re growing up to live in.

We’re not preparing them to be ten year olds if they’re three, we’re preparing them to be three year olds who love being three. If they’re 18 months old at a family session, we’re encouraging them to be 18 months old and not to be five and ready for school. We know that happy faces are the best evaluation, or else miserable faces at the end of the day because they’ve got to go home!

Emily Jones is a trained Forest School teacher, and has worked for many years within a wide variety of EYFS and Primary education fields, most recently as part of an Early Years Consultancy Team as a Children’s Centre teacher with schools, settings and child minders in Yorkshire. In 2006 Emily established the Tinderwood Trust,which brings her pedagogical insights together with an insatiable desire to carry on playing and learning in the woods. More on the Tinderwood Trust facebook page.

Sarah Mason is a photographer who visited the Tinderwood Trust on their annual Conker Tournament event, and documented the day with her beautiful photos. Her blog of the day is here - we think she enjoyed herself thoroughly!