Babies brains are amazing powerhouses that appear to appear to grow in response to creative environments. The reason why children learn holistically and heuristically (i.e. experientially) is because they are going through a unique experience – the young brain makes billions of new connections with every bit of knowledge that is taken in, in order to make sense of it. This process is called synaptogenesis and happens most prolifically between the ages of birth to three.

What is early brain development all about?

The study of brain development is still in its infancy but with the help of neuroimaging (PET, MRI, EEG and NIRS scanners), neuroscientists are starting to discover links between children’s experiences in the early years, their biological predispositions towards certain strengths or interests, and the developing brain. Emerging research shows that babies brains are born with around 100 billion neurons but with only about a quarter of the connections – synapses – already made between them (see the Young Brains report).

Between the age of three and sexual maturity in adolescence, the synapses that are underused start to get pruned out, brain growth slows down, and connections are harder to make in areas that have been pruned, although not impossible. This ensures that the connections that are regularly used get stronger, and those that aren’t used are cut back, so the brain effectively becomes more efficient.

There are windows of ‘plasticity’ later on in life where the conditions for learning are positive and connections can be reformed in the brain. However, the prime time to develop specific knowledge, skills and competencies is in the first few years of a child’s life.

By encouraging creativity and imagination, we are promoting children’s ability to explore and comprehend their world and increasing their opportunities to make new connections and reach new understandings.

Bernadette Duffy, (2006), Supporting Creativity and Imagination in the Early Years, Oxford University Press.

Why are the first three years so crucial for learning?

Research by neuroscientists Shonkoff and Philipps[1] demonstrates that high quality social and cultural experiences are more critical in the early years for the development of healthy brains and well-rounded personalities than at any other time during the rest of childhood and adulthood. These critical experiences include imaginative, creative and cultural opportunities which can help children to build contexts, make meaning and deepen their understanding.

Earlyarts feels strongly about trying to get this right, as far as we know how to, because this web of synaptic connections holds the key to our personalities – it is what makes us uniquely who we are, mentally, physically, spiritually and emotionally, in the same way that DNA makes us uniquely who we are genetically. In short, a healthy and creative environment in the first three years of life, coupled with strong attachment to their significant carers, leads to the development of well-rounded human beings. We don’t know many people who would argue against that!

Where do the arts and creativity fit in?

Given the impact on brain development that early experiences have, it is not surprising that several studies have uncovered significant long-term impacts of creative environments. They highlight how creative activities that encourage positive relationships can support the rapid blooming of synapses, leading to the formation of well-rounded personalities, good attachment, self-esteem and better mental health.[2]

Research shows how some musical approaches can activate the same areas of the brain that are also activated during mathematical processing. It appears that early musical training begins to build the same neural networks that are later used for numerical tasks.[3] In fact, a large body of evidence suggests that music-making in early childhood can develop the perception of different phonemes and the auditory cortex and hence aid the development of language learning as well as musical behaviour.[4]

Because of this, several music education methods, including Suzuki, Kodaly, Orff and Dalcroze are designed to give children stage (not age)-based, structured musical activities from very young ages. The In Harmony programme (based on Venezuela’s El Systema programme) illustrated how a large scale approach to music-making in the foundation years can lead to enhanced academic achievement and engagement in learning, especially for children with special educational needs or those for whom music opportunities would not otherwise have been available.

Similarly, drama and role play can stimulate the same synapses that focus on spoken language; painting can stimulate the visual processing system that recalls memory or creates fantasy; movement, drawing and clay modelling link to the development of gross and fine motor skills. However, we need to bear in mind that the connections between different experiences and different parts of the brain are incredibly complex, far beyond the evidence we have collated here. What we do know about brain development is minute compared to what we don’t yet know.

What happens to children if we get it ‘wrong’?

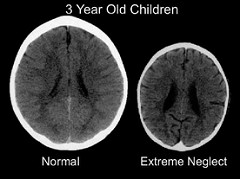

Getting it ‘wrong’ is a highly sensitive term, loaded with social and emotional judgements about what constitutes good or bad parenting, so we will try to offer some responsible thoughts to this phrase. Based on the fMRI images we can access of young babies’ brains, it is a widely held belief that neglect and other adverse experiences (e.g. lack of experiences) in the early years can have a profound effect on how children are emotionally ‘wired’. This can deeply influence their emotional responses to events and their ability to form attachments or to empathise with other people.[5]

It could be surmised from this research that, if children are denied high quality, creative experiences, for whatever reason (entitlement, economics, cultural, societal), the synapses that are predisposed to imagination, auditory, linguistic, physical or creative thinking skills will be pruned, making it difficult to reconnect those synapses further down the line.

This image from the Child Trauma Academy led by Bruce D Perry, MD, PhD, is frequently used to demonstrate the physical impacts of neglect on a child’s brain. The CT scan of the brain on the right is that of a three year old who has grown up in a Romanian orphanage and has been denied the natural sensory experiences of the healthy three year old child on the left, although we don’t have access to the actual case details of these two children. It is considered a strong demonstration of extreme shrinkage due to the harsh pruning activity that has taken place as a result of the lack of stimulating experiences. However, it is also possible that the skull on the right has not formed to the same size as the skull on the left possibly because of malnutrition.

Whatever the story behind these two children’s brains, the fact remains that we owe it to our children to facilitate their best possible experiences of love and learning from the minute we are aware of their gestation in the womb.

You might also be interested in these articles:

- Where is the social, emotional and brain science behind our early education? (Earlyarts, July 2013)

- Babies Brain Architecture (Earlyarts, October 2011)

[1] David, T., Goouch, K., Powell, S. and Abbott, L. (2003)Young Brains, DfES Research Report Number 444: Birth to Three Matters: A Review of the Literature, Nottingham: Queen’s Printer. pp. 117–127.

[2] Zero to Three: Brain Development

[3] Sousa, D (2006), How the arts develop the brain, School Superintendents Association.

[4] Lonie, D. (2010), Early Years Evidence Review: Assessing the outcomes of early years music making, London: Youth Music, p. 13.

[5] Zeedyk, S (2012), Babies brain development.