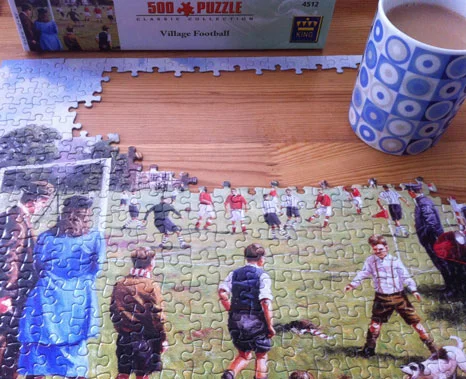

Recently I have rediscovered the (rather addictive) fun of doing a jigsaw with my 10 year old son. Rather like me, he puts on his rose coloured glasses in the face of any challenge and refuses to believe it can't be done. It's the one activity where we sit with our heads so close together whilst staring at the picture, I can hear all the lovely clicks and clacks of his inner world. However, unusually for him, he decided after several attempts that he couldn't do it, declaring, 'This is too hard for me!'

Being a boy who believes that he can do anything he wants with the right tools and resources to hand, and being normally undefeated by jigsaw-type tasks, this struck me as an odd thing for him to say. Later on, his little sister casually sauntered up and, after a quick glance, found three correct pieces in one go and declared, 'This is easy!'. She wasn't trying to undermine her brother (who had long since disappeared with his skateboard), but simply found it engaging and well within her grasp.

On reflection, I realised what was happening. My daughter is a highly visual learner for whom piecing together shapes, colours and textures is second nature. My son, on the other hand, is a more linear, academic learner, who approaches life as if it's a complex mathematic theory waiting to be solved. Jigsaw puzzles just don't require that sort of intelligence, more of an aesthetic intelligence, which is not his forte. That doesn't make him incapable, it's just that this task is unsuited to his preferred methods of learning and doing.

So I was pretty concerned last week to read the long-awaited Henley Review on Cultural Education, with the assertion in 2.3 that 'Schools remain the single most important place where children learn about Cultural Education'. Whilst Henley acknowledges the great role of cultural experiences and opportunities in children's lives, and it is crucial that we realign cultural subjects to have higher status within the mainstream curriculum, the emphasis is without a doubt on culture supporting skills progression for the future economy. It's more about having an education in culture and preparing our children with the skills and knowledge for cultural professions in the future, rather than actually having a cultural education.

For me, the latter is about having a broad based cultural curriculum that focusses as much on the role of culture in the processes of learning as on the subjects and products. Its about the ways in which culture enables all children to build a strong sense of security in their own identity (in its plural sense), to recognise who they are and where they belong in the world. It's also about helping our youngest children enjoy learning through a variety of creative and cultural pedagogies that nurture their learning dispositions, be they logical and mathematical or spatial and kinaesthetic, as Howard Gardner would probably describe my two. This can only happen by having incredible cultural experiences. The sort of experiences that enable them to make meaning of the world around them, that give them a broader contextual understanding, an interest and engagement with the people and places that make up our societies, opportunities to play with ideas, and a real hunger for learning more.

I've blogged elsewhere about the importance that scientific evidence places on the experiences young children are exposed to from birth. Alongside their natural predisposed tendancies, these cultural (or life) experiences have more a significant impact on babies' brain development in the first few years, than at any other time in their lives. Henley even quotes Dame Clare Tickell's report setting out the rationale for how cultural opportunities in the first four years of a child's life enable them to learn and communicate. And yet, there is scant regard for the early years, brushing over these startlingly crucial facts that point to the need for more creative and cultural opportunities from birth in order to help shape children's learning and development as positively as we can, while we can.

Henley's call for more collaborative partnerships with cultural employers, parents and local communities as well as a higher quality of teaching, resources and curriculum is to be praised. I just wonder how much of this is fuelled by a drive for economic reform than by a commitment to creativity embedded within the culture of learning. Not that economic reform is a bad thing at all, but it cannot achieve successful futures for our children in isolation from the much wider cultural issues at stake. I would have thought the by far the best economic policy would be to invest in cultural experiences that directly impact on babies' brains, bodies, minds and potential from birth.

Building skills for the cultural industries and strengthening the professional sector is such a tiny part of this picture. And from where we are sitting, the rest of the jigsaw pieces on the role of culture in building skills for life are proving difficult to find.

Author Ruth Churchill Dower is the Director of Earlyarts