There's something very beautiful in watching a parent take their baby seriously, understanding that their expressions are full of genuine communications, and offering positive responses to stimulate even more expressions, even if they can't quite translate baby's language. Very beautiful and, in fact, often quite hard to achieve because giving babies' communication the attention and integrity it deserves requires space, time, and some serious active listening skills! How many of us have got all three of those available all at the same time? Sometimes we just miss the opportunity when we don't quite 'get' what our baby is saying to us, and anyway, there's tea to prepare, stuff to tidy up, and we really don't want it to look like we don't know what we're doing (as if every other parent or carer always knows exactly what to do...!). Funny to think of it that way, and yet so true. But when it does happen, we know it and we can't ignore the happiness it brings. When we spot that moment of really meaningful communication, and nurture it to a deeper level, our baby responds directly to us, with all the trust, openness, and love of a best friend, and it feels incredibly special.

Other than the natural love affair that sometimes happens between parents and babies, I've also witnessed this in non-language based cultural experiences where shared eye contact becomes the basis of amazing communications. This was beautifully illustrated by Guy Dartnell's production of Oogly Boogly which he reviewed at the Culturebaby conference last week.

But before I get on to that, let me share a superb example of this deep, trusting and open communication happening entirely through dance (courtesy of my very excellent theatre education friend, Jen Harris). Watch how closely Itay listens to the physical expressions of Sophie (his 2 year old daughter) in this dance improv, and how carefully he responds to follow Sophie's lead and keeps open the invitation to continue the game, the shared experience, the discussion, or whatever you want to call it.

So back to our friend Guy whose production of Oogly Boogly also facilitated some lovely conversations, both verbal and non verbal, between toddlers and the performers in the company. The age-range was set at 12-18 months for good reason, as Guy explains;

'The game works well with this age group because the children have a natural desire to move freely and spontaneously, exploring themselves and the world around them with their bodies as the primary means of communication.' I know this was adhered to rigidly as I repeatedly and unsuccessfully attemted to secure a place for my then 2 year old! I was tempted to quote something about children's entitlement to culture at the poor administrator out of sheer desperation to experience this amazing piece, but thankfully I resisted (sighs of relief all round, I can tell you!). Here's a clip of the wonderful Oogly Boogly at Sader's Wells:

Guy stressed that, despite the huge learning potential in each performance, this wasn't intended as a piece of research into what approaches stimulated more or less response, or led to which child development impacts or learning outcomes. Nevertheless, they did notice patterns emerging in terms of a) the amount of space and time needed for a child to feel confident enough to trust the dancer's responsive gestures and to start to play with them, and b) the retained memories of toddlers who came back a second time to the performance and immediately knew what to do (rules of the game) when they stepped inside their inflatable playground.

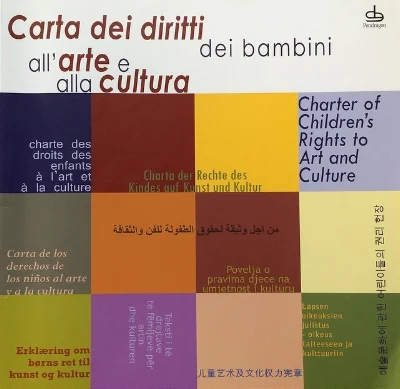

This reminded me of the Children's Charter for Arts and Culture recently launched by the smallsize network for early years performing arts in Europe, which identifies eighteen beliefs about children's rights in 27 different languages. It celebrates the integrity of children's games, even in its introduction:

To us, people who watch and relate to children every day, the word 'game' is absolutely essential because it expresses a vital concept. We all know that children grow up and learn thanks to games and to playing. Playing also means meeting others, creating relationships, taking steps forward. Writing this charter has been a game that allowed us to reflect, weave new relationships and share dreams and deep beliefs.

The charter is available to order from Earlyarts shop and would make a beautiful present with stunning illustrations by children's book artists.

We talked a lot about children's access (or lack of) to culture at the Culturebaby conference, particularly in the context of the Supporting Families in the Foundation Years report. This sets the tone for future early education and childcare services to become much more targeted towards helping children and families to beat cycles of poverty (I talked about the opportunities for theatre to do this in my last blog here). However, we also know that poverty is not simply an economic consequence but also dependent on parental aspirations and on their surrounding cultural environment and opportunities.

It needs a more holistic approach to buck the increasing number of young children falling below the poverty line. Every child deserves the chance to express themselves, build a sense of confidence and assurance in who they, their cultural heritage and their aspirations for the future, not just children in poverty, although it is especially important that we do address their specific needs. So it is very hard to imagine how the impact of cultural services could be measured by their impact only on targeted groups, which is a bridge I fear we may have to cross in the future.

It was a honour for me to sit on the policy panel at the Culturebaby conference, listening to the excellent analysis of the current policy and curricular landscape by Abigail Moss, Deputy Director of the National Literary Trust, and the fascinating research led by Sue Roulstone from the UWE, on the longitudinal project, Investigating the Role of language in children's early educational outcomes.

One of the five key findings was that, children's communication environment influences language development, meaning the number of books available to the child, the frequency of visits to the library [and other cultural venues], parents 'teaching' a range of activities, the number of toys available, and attendance at pre-school, are all important predictors of the child's expressive vocabulary at 2 years. Delegates talked at great length about examples of this already happening in their own practices through creative environments and cultural interventions (speech and language experts using movement and singing for language development, for instance), and the above videos illustrate how that can also happen through non-language based approaches or babies.

In my panel response, I talked about why I believe firmly that the link between creative processes and effective, meaningful learning taking place, should be made more explicit in the revised EYFS. Personally I feel that there is too much emphasis on children reaching a standard level of skills, knowledge and aptitudes which provide them with a 'readiness for school' but may not necessarily be appropriate for a four year old who, as we know, can be at any one of a number of different stages of development, and who should never be made to feel in any way inadequate for being four, whatever the expectations of the setting they find themselves in.

It is hugely important to recognise the expertise and professional judgement of early years practitioners and professionals around the child, who know them best and have their broader contexts and cultures in mind. They have seen each child's individual progress over much longer periods than can be displayed in a short assessment on entry to school, and it will be great to see their judgements deepened through discussions with parents and carers at the Two Year Old report. The current proposal is to restrict this report to the three prime areas of learning, but personally I feel this should incorporate the specific areas as well (especially expressive arts and design), to reflect a child's holistic developmental progress, and to ensure specific cultural interventions that have had a positive impact from birth are not excluded.

For instance, music and singing has long been celebrated as one of the earliest forms of communication and language development between parents / carers and babies, backed up by substantial evidence of its positive impact on early brain development. In the proposed EYFS assessment framework, it is identified under a specific area as a subject rather than a process for learning and therefore may be considered unnecessary to introduce until the age of three. Watch this space on that one!

At the end of the day, our teachers, early years, childcare, and early intervention professionals are doing the most important job in the world and need to be properly supported in this through the training, resources, leadership processes, and frameworks through which they operate. This needs to include cultural interventions that focus on creative processes, experiences and pedagogies that enable both the adult and the child to realise their full potential and strengthen their cultural capital.

Author Ruth Churchill Dower is the Director of Earlyarts

Photo courtesy of Oogly Boogly, taken by Benedict Johnson